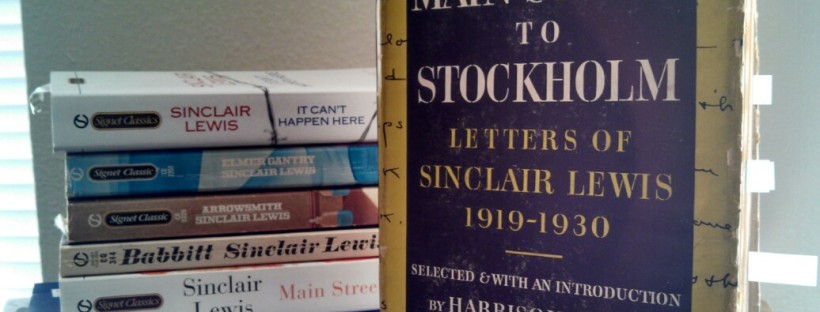

“From Main Street to Stockholm: Letters of Sinclair Lewis 1919-1930” edited by Harrison Smith, 1952.

BOOK REVIEW: From Main Street to Stockholm: Letters of Sinclair Lewis 1919-1930 edited by Harrison Smith, 1952 (full text on the Internet Archive).

“[D]on’t be such a damn fool as ever again to go to work for someone else. Start your own business,” the 34-year-old Sinclair Lewis advised his friend Alfred Harcourt. “I’m going to write important books. You can publish them. Now let’s go out to your house and start making plans” (p.xi). That business became the publishing house Harcourt, Brace, and Company, and the next year, in 1920, it published the book that made Lewis famous: Main Street. Thus began the decade-long trip from the prairies of Minnesota to Stockholm, when Lewis was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

As the only volume of Lewis’ letters, From Main Street to Stockholm was published in 1952, the year after he died, and collects together his correspondence with Harcourt’s publishing house. Given their relationship the letters just as often pertain to business as they do Lewis’ European travels and the politics of the literary world. While the reader may not close the book with a richer understanding of Lewis’ psychology, they will have witnessed an iconoclast at work. Through these letters one follows Lewis through the “Big Five” and the public’s response, from Main Street (1920) being declared the most monumental book of the century to Boston’s District Attorney banning Elmer Gantry (1927) from the city. (As a response to the latter, we find out, Lewis and Harcourt forewent a lawsuit and instead bought billboards capitalizing on the controversy … at a Methodist convention in Kansas City).

What stands out the most in his letters is his self-confidence and keen sense of what will stick in the public mind. One sees firsthand, for example, the amount of care he took in naming his character. Writing about a middle-class businessman and booster, he considers Pumphrey and later Fitch but at last settles on a name he predicts will enter the lexicon (and it did)!

The name now for my man is George F. Babbitt, which, I think, sounds commonplace yet will be remembered, and two years from now we’ll have them talking of Babbittry (12/17/1920; p.57).

Here and elsewhere his confidence is prescient. Even while still working on the manuscript for Main Street he doesn’t hide his ambition. Anticipating the book’s success he asks,

Would it be perfectly insane and egotistic to suggest that you .. send a copy of the book to the [Pulitzer] prize committee, suggesting that the dern thing is a study in “the wholesome atmosphere of American life” etc. (11/12/1919; p.18)?

And he’s writing that before the book’s even finished.

“You mustn’t suppose … 70,000 [words of Main Street] means it’s almost done though. I’m afraid I shall be doing well … if I keep it down to 180,000 words, even after cutting first draft” (12/15/1919; p.19).

One shares in Lewis’ joy when at last the book is published and, as he snoops around book stores to eavesdrop on what people are saying, Harcourt is rushing to get more off the press. None of this confidence wanes over the years and by 1925, with the publication of Arrowsmith, Lewis wonders if it will be the book that finally gets him the Nobel Prize. Someday–but he’s still got a few years to go.

Interestingly, for as much as Lewis dreamed of these major prizes almost nothing is said of the two he almost received. As the events unfolded, nothing was said of the fact that both Main Street and Babbitt were chosen by the Pulitzer Prize committee and both were vetoed by the Columbia Board of Trustees that oversee it. It’s only when there are rumors of Arrowsmith winning the prize that he acknowledges these “matters”:

I hope they do award me the Pulitzer Prize on Arrowsmith — but you know, don’t you, that ever since the Main Street burglary, I have planned that if they ever did award it to me, I would refuse it, with a polite but firm letter which I shall let the press have, and which ought to make it impossible for any one ever to accept the novel prize (not the play or history prize) thereafter without acknowledging themselves as willing to sell out. There are three chief reasons — the Main Street and possibly the Babbitt matters, the fact that a number of publishers advertise Pulitzer Prize novels not, as the award states, as “best portraying the highest standard of American morals and manners” or whatever it is but as the in every-way “best novel of the year,” and third the whole general matter of any body arrogating to itself the right to choose a best novel (4/4/1926; p.203).

The next month when it was announced he’d in fact won the prize, that’s exactly what he did. Over the next five years, two more novels followed, their successes culminating in his being awarded the 1930 Nobel Prize in Literature. But upon achieving the success he predicted, it wasn’t enough and he was letdown by how Harcourt handled the news. In one of his last letters to the publisher, he writes as both a disappointed author–and a hurt friend.

To put it brutally, I feel that the firm let me down, let my books down, in regard to the prize award. It seems to me that you failed to revive the sale of my books as you might have and that … you let me down as an author by not getting over to the people of the United States the way in which the rest of the world greeted the award. It would have meant the expenditure of considerable money on your part to have done this, but never in history has an American publisher had such a chance.

… If you haven’t used this opportunity to push my books energetically and to support my prestige intelligently, you never will do so, because I can never give you again such a moment (1/21/1931; p.300-1).

Harcourt’s final words are moving:

I know you have some idea of how sorry I am that events have taken this turn. You and we have been so closely associated in our youth and growth that I wish we might have gone the rest of the way together. If I’ve lost an author, you haven’t lost either a friend or a devoted reader (2/3/1931; p.302).

In the end, the book’s a wonderful case study of the relationship a writer has with their publisher. These letters show us firsthand everything that goes into the writing process, from hard work and support to, yes, an insatiable ego. Turning the last page, one finds they’ve walked with Lewis and Harcourt the long road from Main Street to Stockholm, and even if it ends with a sigh, along the way neither needed to stop to catch their breath.

From Main Street to Stockholm: Letters of Sinclair Lewis 1919-1930 is available for free on the Internet Archive here.

Every weekend i used to pay a visit this site, because i wish for

enjoyment, for the reason that this this web page conations truly good funny stuff too.

LikeLike