It Can Happen Here by Claire Sprague

With the presidential candidacy of Donald J. Trump, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that there’s been a renewed interest in Sinclair Lewis’ novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935). For those unfamiliar with it, it’s about the rise-to-power of a Depression-era demagogue named Sen. “Buzz” Windrip who becomes president with a campaign based on religious zeal, patriotic fervor, and economic distress. Once in office Windrip exercises broad executive authority, going so far as to create a paramilitary force a la the Nazi SS. This he uses to, among other things, terrorize and suppress the media. To put it briefly, It Can’t Happen Here is the story of how “when Fascism comes to America, it’ll come as a cross wrapped in the American flag.”

One wishes the circumstances were different, but I think it’s exciting to see more people engaging with Lewis’ novel. Several bookstores I’ve been to recently have it placed prominently in their “staff picks” sections, and, in Berkeley, a stage adaptation is gaining a lot of media attention. Hopefully all of this will lead readers to see that American fascism was just one of many things Lewis scrutinized–after all, he also addressed American provincialism, capitalism, and (my favorite) evangelism.

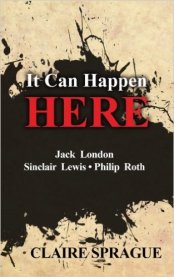

Although It Can’t Happen Here is one of the most-famous American dystopian novels, Lewis is not the only author (nor even the first) to have written about this topic. In fact, this is something I once discussed in a short review-essay published in the Sinclair Lewis Society Newsletter (Spring 2015). The book I reviewed was titled It Can Happen Here, a literary study that compares and contrasts Lewis’ novel with the works of Jack London (The Iron Heel, 1908) and Philip Roth (The Plot Against America, 2004). I have included below an excerpt, though you can read the full essay here.

With Election Day approaching, I’m optimistic our country will make the right choice, but as Lewis argued (and which Sprague expands upon in her own book), we should never be so bold as to say “It can’t happen here.”

In a new study of the American dystopian novel, CUNY professor emerita Claire Sprague writes in It Can Happen Here (Chippewa Books, 2013) that even though fascism never took hold in the United States, “the potential was and still is [h]ere” (99). To support this, the author turns to Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1908), Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here (1935), and Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004), each of which demonstrated that the threat is not an “invading army or ideology but … native fascist movements” (96). What is unique to these books is that they are not the dystopias of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) or Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron” (1961), tales of a distant future, parables of how all utopias are undermined by the worst of man and dystopias by his best, but instead are rooted firmly in the present. To a contemporary audience, these were cautionary probes into the near future. Some could even call them propaganda.

According to Sprague, the emergence of the dystopian novel was an aberration, an historical response to the changing circumstances of the late-19th-century. Although visions of Utopia existed prior to Thomas More’s coining the term in his 1516 book by the same name, the notion of utopian communities was carried to the New World, and by the author’s estimation fomented by, European naturalists imagining the landscape as a new biblical Eden. As this spirit took hold, the first century of the Republic was “a time when to think of the good society was to try and create it” and thus during this period “Some one thousand communes were founded in America,” including Robert Owen’s New Harmony and Upton Sinclair’s famous Helicon Home Colony (10). The literature this inspired, including Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000-1887 (1888), depicted a society free of want and poverty. Yet, as the disparities of an industrializing nation grew and the United States expanded into Cuba and the Philippines, these visions reversed. Sprague identifies this shift with H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1895), where the future is radically divided between social classes (so much so that one is literally monstrous), and notes that “If the twentieth century represents the coming of age of dystopia, then Wells is dystopia’s precocious prophet” (11). In his stead then were London, Lewis, and Roth, each sharing their own visions of dystopia. To these writers, they did not need a time machine to see the descent: They had only to look into the eyes of their neighbors. […]