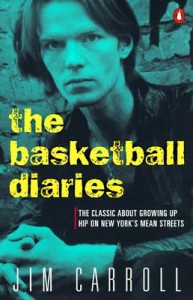

BOOK REVIEW: The Basketball Diaries by Jim Carroll (1978)

First published in 1978, The Basketball Diaries by Jim Carroll is a slightly-fictionalized account of growing up in New York City. Spanning the Fall of 1963 (when he was 12) to the Summer 1966, the reader follows Carroll as he wanders the streets, shoots heroin, and makes love. Although much has been made of his drug and sex life, which in fairness is most of the book, what’s often overlooked are the themes that slowly rise from his experiences. Rather than being merely “the classic about growing up hip on New York’s mean streets” (the person who wrote that should be imprisoned) it’s an account of maturity – sexual, emotional, and even political. As these all run parallel, they soon converge at a point that transcends any one person’s experiences: we are our lost innocence.

Diaries is at some points funny, at others discomforting, but it’s an opportunity for you and I to look in on a lifestyle that, I’m presuming, is foreign to many of us. The fact that Carroll is able to write of it so well by blending the sensual with the indulgent is a testament to his abilities as a punk poet. This is the first of Carroll’s books that I’ve read but I’m planning on checking out his other work (he has two memoirs and at least two books of poetry).

Rather than his diary being merely a tally of his adventures, what I found the most fascinating was his burgeoning political consciousness. In his early entries Carroll’s politics don’t extend past his disdain for the police and the occasional red-baiting he faces because of his long hair. It’s not until he turns 15 that this changes. Slowly, reflecting upon his childhood memories, a certain awareness creeps into his writing.

I used to have horrible dreams of goblins in tiny planes circling my room and bombing my bed most every night age six or seven; every time a fire truck or an ambulance passed the house I was pissing with fear in my mother’s arms with the idea that it was the air raid finally come …. (Fall 1965; 126)

Yet it’s a complicated fear. Growing up in Manhattan, he has always lived “within a giant archer’s target … for use by the bad Russia bowman with the atomic arrows.” This thought at one point gives him “a strange rush of unknown sex giddiness” and what follows is an example of his more colorful prose.

I thought of the explosion’s eye as one giant plutonium red cunt that would suck me up and in and just totally devour and melt me into its raw wet walls of white heat in pure orgasm. (Fall 1965; 114)

This relationship with death doesn’t subside and Carroll merely learns to live with it. In fact, life on the archer’s target was a plateau where he annihilation was inevitable but he hoped the end could be pushed back a few days or weeks at a time. For example, expecting the worst from the Cuban missile crisis he hoped “we could delay taking action on the … crisis so I’d play in a really important basketball game on a Friday night.” Years later, having grown into a young writer, this hasn’t changed much:

I don’t give a screw about … basketball games two weeks from now. It’s just gotten bigger now … will I have time to finish the poems breaking loose in my head? Time to find out if I’m the writer I know I can be? How about these diaries? Or will Vietnam beat me to the button? (Winter 1966; 151)

It’s in this new mindset that he also becomes aware of his own writing – he needs to write. Poetry for Carroll is “just a raw block of stone ready to be shaped” and he wants to be the one to shape it (Winter 1966; 159). Thus throughout Diaries we see the coming-of-age of not only a man but a writer. We see the loss of innocence, which we ought not mourn, and from it we see a maturity that is overtly political and proudly resistant. Yet even as witnesses to this metamorphosis, Carroll waves his hands and says something telling: the central character of his personal diary was never him but “this crazy fucking New York.”

Soon I’m gonna wake a lot of dudes off their asses and let them know what’s really going down in the blind alley out there in the pretty streets with double garages. I got a tap on your wires, folks. I’m just really a wise ass kid getting wiser and I’m going to get even somehow for your dumb hatreds and all them war baby dreams you left in my scarred bed with dreams of bombs falling above that cliff I’m hanging steady to. (Winter 1966; 159-160)

I really like this entry because it’s a conscious shift from the inward to the outward. His diary is now about more than just himself. It’s a letter to the city. Although spiteful, Carroll now understands that even introspection is society studying itself. With this in mind he wants to be more than some expose on the seedy underground, a catalog of injustices. His writing is now a weapon and his diary a mirror to the city, the nation, the world.

2 thoughts on ““The Basketball Diaries” by Jim Carroll”